Note:

“Tautology: a statement that is true by virtue of its logical form.”

Tamponade, oddly, can be harder to define than tautology!

Of course, many people say things like “tamponade is defined clinically,” or cite a cut-off level of pulsus paradoxus. But such criteria can be either vague, arbitrary, or poorly supported by good evidence. (For a good review of myriad such issues, check out Misconceptions and facts about pericardial effusion and tamponade. Paywall – sorry.)

A lack of IVC plethora rules out tamponade... right?

Instead, focus (FoCUS?) on a simpler element of defining tamponade – the IVC. A large number of textbooks and reviews have stated that plethora of the IVC is a very sensitive feature of tamponade. For example, a beautiful recent handbook of focused ultrasound states that:

“If tamponade is a consideration, it may effectively be ruled out by demonstrating of 50% or more with deep inspiration without having to pursue more sophisticated echocardiographic techniques.”

“If the IVC is collapsing, you are almost certainly not dealing with tamponade.”

Let’s see a case, though, to point out the complexities behind such blanket statements.

Case: Recurrent pericardial effusion s/p pericardial window.

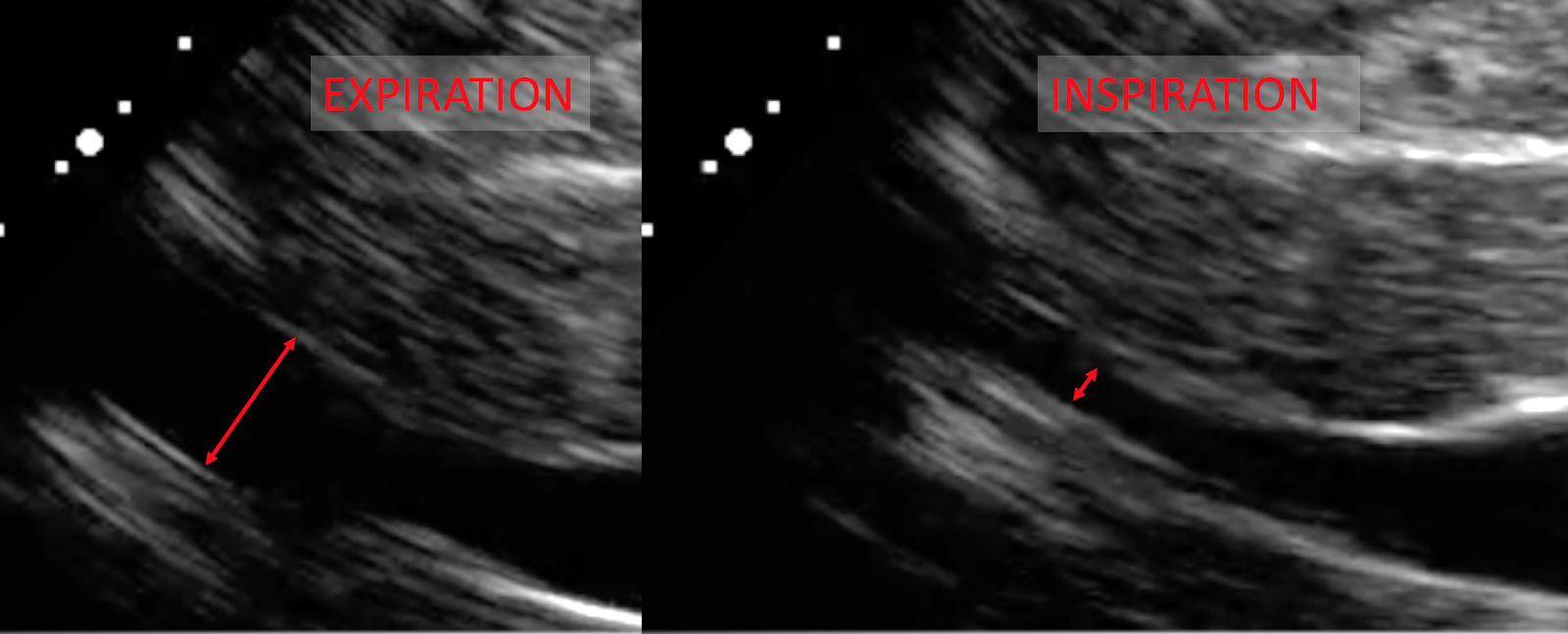

A patient presented to the ED with positional chest pain. However, she also had a recent history of pericardial effusion subsequent to a CABG. Although she had undergone a pericardial window at that time, and although her vital signs (aside from a modest tachypnea) were normal, the ED physician performed an echo. First, the sagittal and transverse views of the IVC:

Sagital

Transverse

And the clip:

The transverse images show that the IVC diameter is just < 2.1 cm, and collapses just about 50%. The sagittal images, however, demonstrate a much higher degree of collapse in the proximal IVC. Based on these views, could we have ruled-out tamponade?

Well, here are the rest of the views of the heart.

Significant effusion – check.

RV collapse in diastole – check.

RA collapse in systole – check

Large respiratory variation in the MV inflow – check!

So, is this tamponade? Heck, yes! The next day she had 700 ml worth of effusion aspirated, with an initial intrapericardial pressure of 24 mm Hg. Pretty diagnostic.

But isn’t IVC plethora supposed to be almost 100% sensitive for tamponade?

Technically, 97% sensitive. Almost every textbook or review that gives this figure cites the same 1988 paper by Himelman et al., and it is imperative to understand the methods of that study before repeating that “almost 100% sensitive” claim.

Himelman et al. defined IVC plethora as < 50% IVC collapse during a deep inspiration, measured 2 cm distal to the RA entrance. So, plethora was not seen in our patient - was this a “miss” for detecting tamponade?

Well, Himelman had defined tamponade in a pretty narrow sense. They required that either:

a) The diastolic filling pressures (i.e. the diastolic pressure in the RA, RV, etc.) had to all be > 12 mm Hg), and be within 5 mm Hg of each other;

or

Given this definition, our patient did not have tamponade during the ED evaluation! **

There is a circular element to the inclusion criteria and the outcomes here...

The tautologic definition of tamponade is tautological.

Let’s dwell on Himelman’s definition of tamponade a bit more, and implications for the results they found.

They only included patients with either overt hypotension from their effusion, or patients with RAP ≥ 12 mm Hg. Of the 33 patients found to have tamponade, 20 had a RAP > 12 mm Hg. The ASE guidelines above, then, suggest that most of these patients would be expected to have an IVC that was fat and plethoric. And vice-versa: patients with a plethoric IVC would be predicted to have RA and intrapericardial pressures > 10, and likely > 12 for many of them.

Tautology: If we define tamponade as RA pressure > 12 mm Hg, any sign that defines a high RA pressure (IVC collapse < 50%) will be very common, by definition!

Put another way, if you say that (based on Himelman) a non-plethoric IVC rules out tamponade, but only if you define tamponade such that the IVC should be plethoric.

But isn’t that a common-sense part of defining tamponade; JVD, pulsus, and hypotension? Well, it turns out that tamponade can be defined in many different ways.

There is more to tamponade than the end-stage, “clinical tamponade” presentation.

Studies of pericardial tamponade have used a variety of definitions of tamponade. And when different definitions of tamponade are used, the utility of IVC plethora (or JVD, which we can use as a clinical surrogate for IVC plethora) will vary as well. For example:

A 1995 study defined tamponade as an “effusion causing dyspnea which is relieved by aspiration of the effusion,” and found that 87% of patients who received pericardiocentesis had significant relief of dyspnea. But half of the patients who fulfilled their definition of tamponade had no JVD (they did not evaluate IVC plethora).

A 2006 study looked at patients with pericardial effusions, all of whom received both right-heart catheterization and pericardiocentesis. Tamponade was defined solely as equalization of RA and IP pressures. They found that 24% of the cases of tamponade showed fairly low RA and IP pressures (< 7 mm Hg) prior to pericardiocentesis. Accordingly, only a fifth of these “low-pressure” cases of tamponade presented with JVD. This suggests that IVC plethora would have been correspondingly low as well, but echo results were not included, sadly.

A 2012 chart review also used a broader definition of tamponade than had Himelman (any of following echo features: characteristic RA, RV, or LV collapse; characteristic variation in blood flow through the TV or MV, or dilated IVC with lack of inspiratory collapse). Only 13% of these patients had a dilated, plethoric IVC.

Well, those studies didn’t look at “real” tamponade.

Because of studies like those just summarized, a subset of tamponade, know as “low pressure” tamponade, has been more widely recognized. Often seen when a patient with a pericardial effusion is also hypovolemic (e.g. from diuretics or illness), a low-pressure tamponade nonetheless manifests with the symptoms and hemodynamic characteristics of “real” tamponade. JVD, pulsus, or overt hypotension, however, may be initially absent.

In fact, many experts have tried to push the view of tamponade as a spectrum, with broader inclusion criteria. Instead of a binary diagnosis of tamponade, we ought, they argue, to be evaluating where the patient is on the spectrum, as well as their potential to move “up” that spectrum; i.e deteriorate.

The IVC is but a single data point

In our patient, a modest degree of tachypnea, as well as a classic echo profile suggested that this patient was in echocardiographic tamponade, and at risk of deteriorating. If the non-plethoric IVC had been used to classify our patient simply as “not real tamponade,” the patient could have received less scrutiny, delayed evaluation, and perhaps a poorer outcome.

But this is nothing surprising, really. Almost every disease comes on a spectrum, and tamponade is no different. Accordingly, it isn’t useful, and may indeed be harmful, to teach that the IVC can “rule out tamponade.”

__________________________________________

** Yes, the intrapericardial/RA pressure was higher the next day, when directly measured during aspiration. However, the procedure was about 1 day after the echo. In that interval probably more fluid had accumulated in the pericardium. The patient had also received > 2 liters of IV fluids before the procedure. IV fluids have frequently been shown to worsen a “low-pressure” tamponade, sometimes converting into the more conventional, hypotensive sort!